In the decades leading up to the Global Financial Crisis in 2008, globalisation was heralded as an economic phenomenon that worked to the benefit of all – whether an economic giant like the USA, or an emerging economy like Vietnam. However, since the financial crisis, political populism arising from both the Left and the Right has called the benefits of globalisation into question. From Donald Trump’s campaign for the White House, to aspects of the Vote Leave argument for the UK to break from the European Union, the notion of free trade and the advancement of globalisation has come under fire.

We’ll be taking an objective look into the topic using publically available information from the World Bank, OECD, Bank of England and the Federal Reserve to find out: who are the winners and losers of globalisation?

Measuring globalisation

Globalisation, the result of encouraging an increase in both imports and exports, allows economies and nations to specialise in particular sectors, goods, products and services, helping both relatively poorer and relatively richer countries to earn a place in the global market. Examples of this are far-reaching—from the UK’s dominant financial services export industry, to Saudi Arabia’s notable role in the global oil market. For poorer, smaller countries, globalisation has given them a leg-up through trading low cost wholesale goods such as consumer electronics, clothing and raw materials that are kept cheap by low domestic labour rates.

The ‘beginning’ of globalisation is a disputed topic, but for the purposes of our analysis we’ll be looking at the period from 1960 up to the present day. We’ve chosen this time period for two reasons: firstly, because the sharp fall in transportation costs following the technological advancement of World War II allowed countries far and wide to be easily accessed and secondly, because records and data detailing international trade are only really reliable from that period onwards.

To measure the effects of globalisation, we’ll be looking specifically at the extent to which international trade contributes to an economy’s domestic output (effectively, the percent of GDP that is made up of imports and exports).

The winners of globalisation

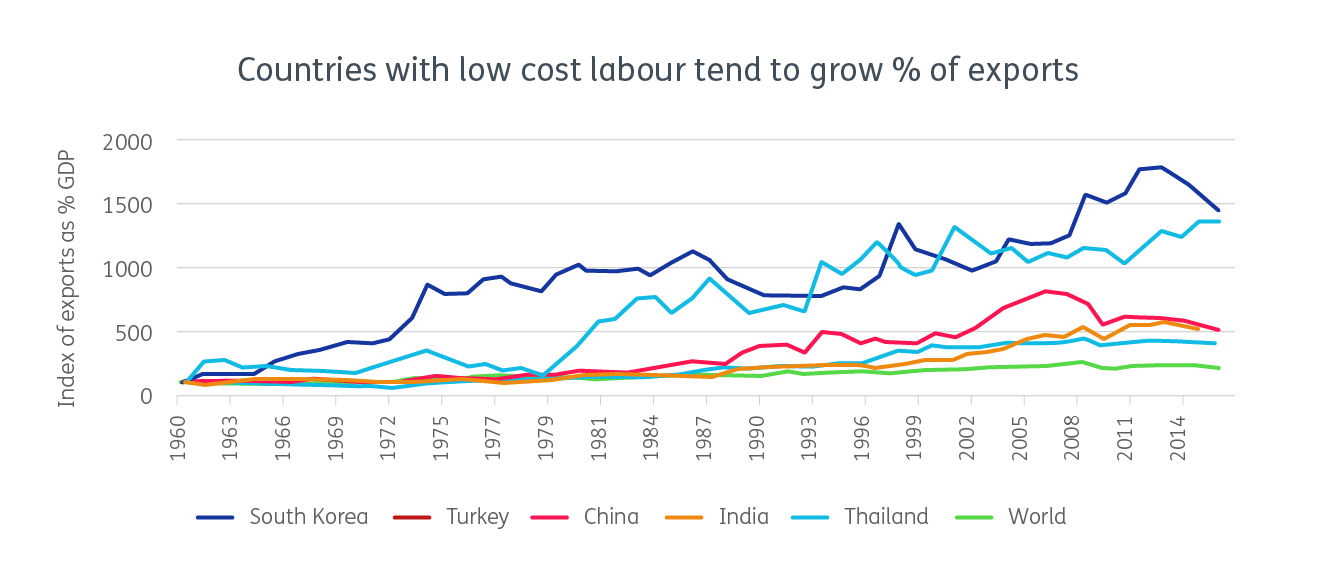

Over the past 50 years, while many economies have been maturing, stagnating or even shrinking, there are many which have been able to exploit global markets and swell GDP, in part, due to their growing export sector.

Source: World Bank / World First Data

Over the past 50 years, the world’s dependency on the sum of exports has more than doubled, primarily as a result of eastern economies gaining access to the global marketplace and increasing revenues generated from exports. Beneficiaries of this effect have been South Korea, Turkey, China, India and Thailand, all of which have been able to grow strongly as a direct result of increased exports.

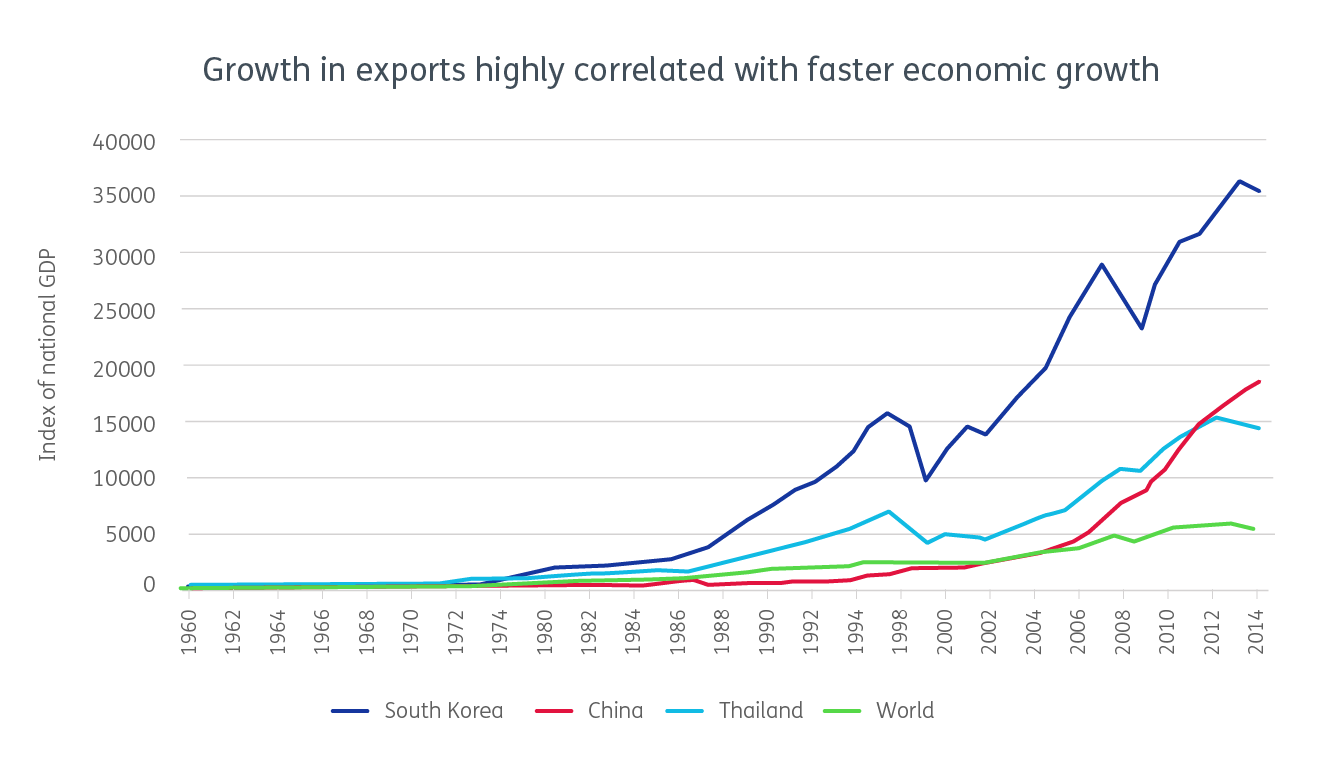

Source: World Bank / World First Data

The losers of globalisation

Finding a so-called ‘loser’ of globalisation on a country-by-country level is difficult. Globalisation doesn’t necessarily leave countries behind or out of step, but does incentivise so-called specialisation where, instead of a country producing and manufacturing all the goods and products required to meet demand within their borders, the consumer will favour cheaper goods made and produced overseas.

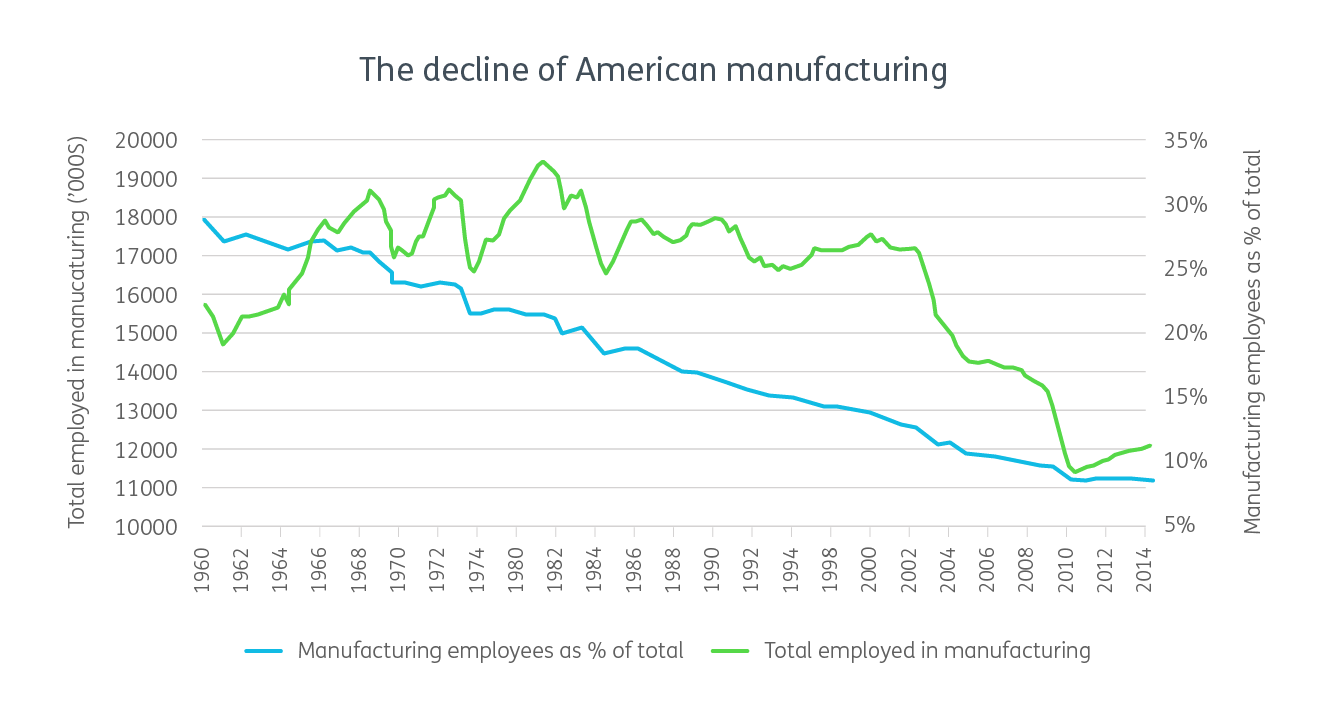

When the balance begins to shift toward those foreign-made, cheaper goods and services, this can be detrimental to those who would have provided the goods had importing them not been an option.

Source: FRED / World First Data

This will be a familiar scenario to those who worked in manufacturing in the USA over the past 50 years. As shown above, the number of workers employed in the manufacturing sector have fallen sharply. Not only that, but the percentage of the American labour force that work in manufacturing currently sits at its lowest level in recorded history, making up just 9 percent of all jobs, down sharply from 39 percent in the sixties.

Will globalisation continue?

After being one of the most prevalent economic trends of the past century, globalisation’s benefits are now being called into question across the Western world. This is exemplified in the Donald Trump presidential campaign and the rise of populist politicians across mainland Europe. The common factor behind these political shifts lies with those who believe they’ve gotten a rough deal from the lowering of borders, the falling tariffs and increased global trade. The core of Donald Trump’s support has been from working class blue collar workers and those who feel displaced by the shift of industry to cheaper cost centres.

Long-term economic patterns don’t tend to go out with a whimper but a bang, and should globalisation come to end, it’s unlikely to be due to old age. While a resounding anti-globalist political party is yet to take charge in any significant way, polling from the USA to Greece has shown a rise in support for such movements. We may not be too far away from globalisation facing its first major political hurdle.

And what if the tide turned against globalisation?

To say a populist uprising against globalisation would have far-reaching effects is an understatement. More mature economies, like the USA and Western Europe would receive a dose of heavy inflation as they’re forced to produce primary goods domestically, but at a far higher price. Capital allocation would also have to be adjusted sharply, hurting industries with high R&D costs like healthcare and high-end technology. At the other end of the spectrum, export led countries like South Korea and China would find their products left without a consumer, hitting GDP and even prompting a protracted economic downturn that would last however long it took those economies to adjust to a more domestically focused, closed off future.

Related reading:

SMEs bear the brunt as post-referendum reality starts to kick in

The Think Global Guide to Exporting

How to finance an export business