A Deal is a Deal, Or Is It?

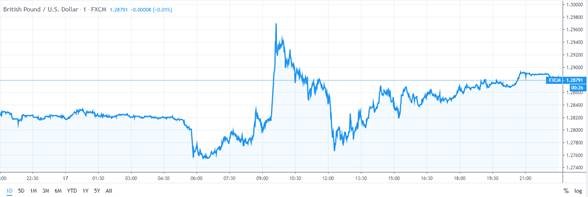

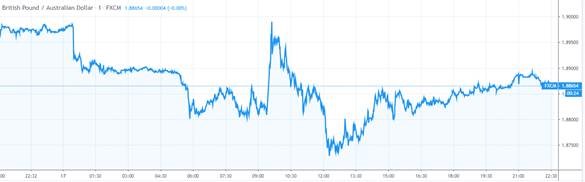

Boris Johnson has secured the backing from EU leaders on his final departure agreement which is set to take the United Kingdom out of the European Union on the 31st of October. But it hasn’t come without its obstacles. The initial market reaction saw a positive bid on Sterling against the board. Cable was up two big figures, tracking the 1.30 handle and GBP/AUD saw a similar move. That said, the move was short-lived, as Sterling began to sell off the back of the news that the Democratic Unionist Party was ruling out its support for the agreement. This saw a heavy sell-off in Sterling. We have spoken a lot about ‘the deal’ and the implications it has for the UK economy. It was clear from early on that Johnson and his supporters never liked Theresa May’s proposition. So what has changed? Below is a breakdown of some of the material changes that have been agreed between Europe and the United Kingdom yesterday evening. The below two charts paint a clear and obvious picture as to how the events unfolded. The correlation is something we see very rarely in currencies.

GBP/USD 1 Day Chart

GBP/AUD 1 Day Chart

So what is the new agreement?

Northern Ireland

In essence, the border of Ireland was the key tipping point for this deal being secured and is the biggest significant change to the existing deal. Under Theresa May’s plan, the whole of the United Kingdom would have remained in a customs union with the EU to prevent a hard border in Northern Ireland. There would also have been regulatory alignment for goods crossing from the UK to the European Union. This, Brexiteers claimed, would have effectively trapped the UK in the EU even though it had left and restricted the ability to strike new trade deals. Under the new arrangement, the backstop has been restricted to Northern Ireland only. In legal terms, Northern Ireland will remain inside the UK’s customs territory – but in all practical aspects, it will follow EU customs rules. Goods crossing from Britain to Northern Ireland will pay any applicable EU tariffs although there will be a mechanism to claim them back if they end up on the Northern Ireland market. Northern Ireland will also follow all EU single market rules and regulations for goods while the rest of the UK will be free to diverge.

Consent

This is a completely new element to the agreement struck by Mrs May. Under the plan, after the new backstop arrangement has been in place for four years, the Northern Ireland assembly will be asked to give its consent to its on-going operation. However, critically, it will be enough for a simple majority of assembly members to back it, for it to continue for another four years. This means that the DUP, who do not have a majority in the assembly, will not be able to veto it. They had demanded this as the price of their support but was something Mr Johnson was unable to deliver for them. That was the principal reason they rejected the deal.

Customs Union

Mrs May’s deal envisaged the UK-wide customs union in the Irish backstop as a “bridge” to the future relationship with a commitment that became the focus for Conservative Eurosceptic opposition to it. The version of the political declaration that she agreed with the EU in November last year committed to “build and improve on the single customs territory provided for in the withdrawal agreement”. The EU regarded the commitment as a promise that Britain would join a “customs union plus” with high alignment to single market rules. This has now gone.

What is the same?

Despite suggestions that the UK would not want to participate in EU agencies – such as the medicines regulator – there is no suggestion of this hard line in the revised political declaration. The UK says it is also keen to continue cooperating on defence, crime and space development. There is also talk of participation in the European Space Agency.

In short, the changes to the political declaration are less than might have been anticipated. And certainly, less than Mr Johnson once implied.